Depends on what you find. If you find a hairline break on a flexible copper trace, you'll need to scratch off the clear coating to get down to the copper, then bridge the break with a blob of solder. We used to run into this a lot with older tvs. To prevent a repeat failure, use a small hot soldering iron, melt a little solder on each side of the crack, then go back and melt in a piece of wire. I use a long piece so I have something to hold onto, then you can cut off the excess when you're done. It only needs to be a quarter inch long. If you don't put that wire in there, a crack will form in the solder over time.

Heat is the deadly enemy of transistors, and it can damage the plastic with the copper traces in it. Many people think it's safer to turn down the temperature on their soldering iron, but that is what leads to the damage. It takes so long for the solder to melt, that by the time it does, the damage has had time to occur. With a nice hot iron, the solder will melt quickly so you can get in, get out, and get it over with before much heat makes its way into the plastic.

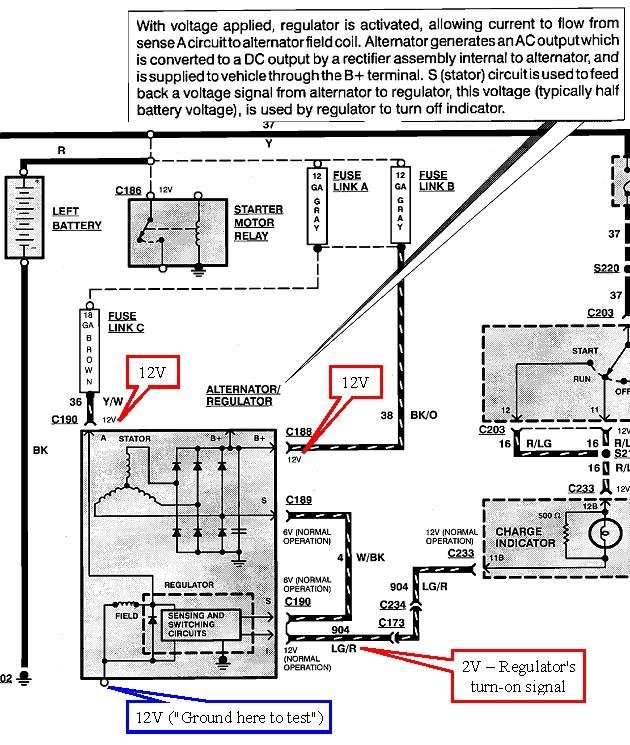

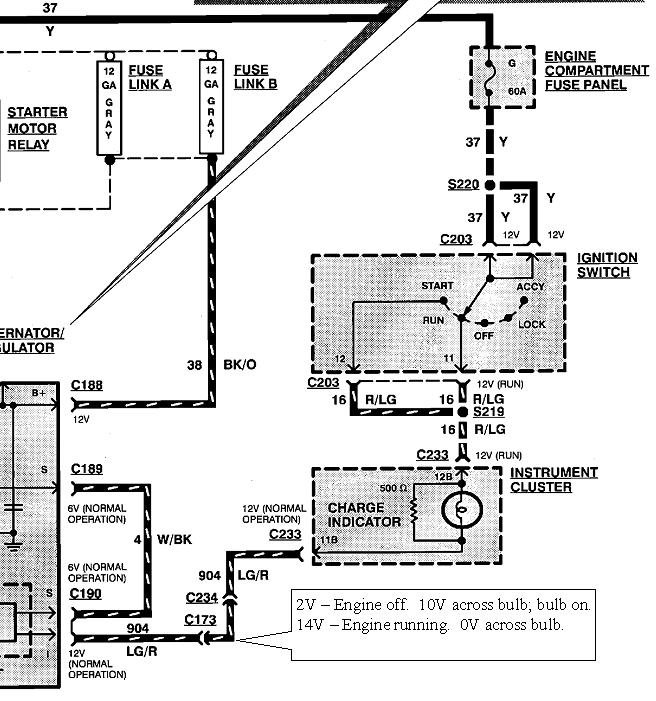

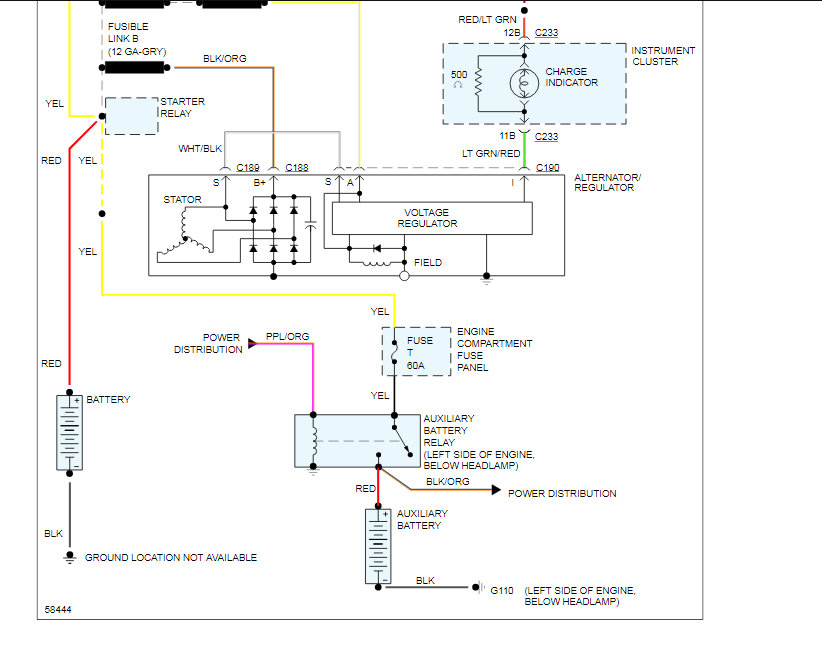

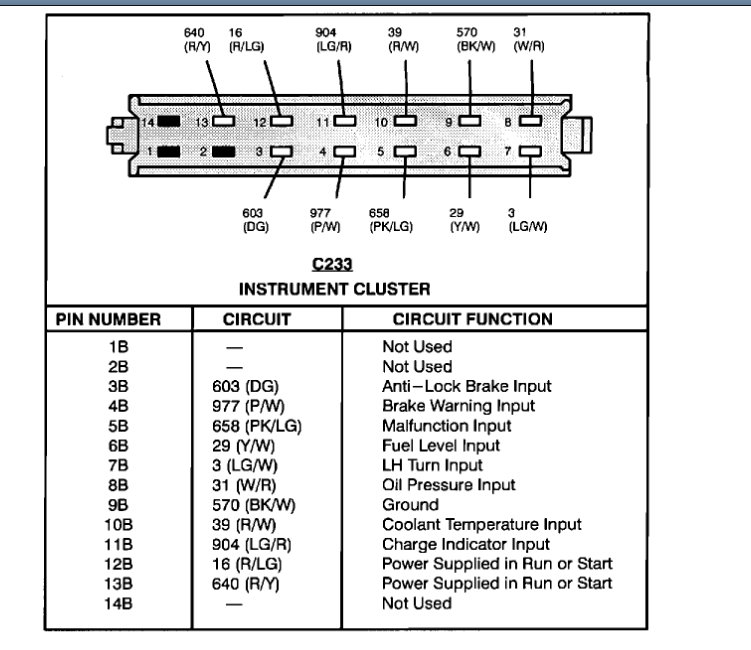

Once you've seen one of these breaks and know what they look like, they're usually pretty easy to spot. Most of the time they occur where the copper trace becomes real narrow, or where the flexible print bends around a corner. This is real common today on a lot of rear tail light housings too. If you don't see a break, use your ohm meter to measure the two circuits. Start at the "Battery" light bulb socket, then follow each trace back to a connector terminal. Those are the points to measure for continuity. You can check the bulb too, but there is about a 500 ohm resistor next to the bulb to provide an alternate path for the regulator's start-up signal if the bulb burns out.

GM trucks have the same kind of flexible plastic sheet stuffed into the opening where the instrument cluster's plug slides in. If you have something similar, look at the plug on the cluster, and you should see the terminals are spring-metal strips. Lightly sand those shiny, then use a small pick to pull those strips out a little so they put more pressure on the flexible print. Lightly sand those bare copper terminals on the print too.

Chrysler uses pins crimped to a hard, regular circuit board on the back of the cluster. On older vehicles, you hold the cluster up to the dash, then reach behind it to connect two plugs. On newer models, those terminals sit in a plastic box with angled sides that guide the plug into it as you slide the cluster into the dash. Those terminals are soldered to the circuit board, but they are well-known for developing broken solder connections. Those were a big part of what kept us in business at the tv repair shop. I only repaired one of these clusters, and I can't remember if I had to unbolt the circuit board and flip it over to see the broken connections. It seems to me it wasn't that difficult or time-consuming. This type of circuit board usually has copper traces on both side, and part of a circuit on one side is connected to the other part on the other side by lining the hole with copper. Once the terminal is inserted and it is soldered, that solder flows along the copper to show up on both sides of the board. You can get pretty aggressive with the soldering iron on those. You'll see the solder melt, then add a little new solder to the joint. The flux in the new solder will help it to melt the old solder on the backside of the board, so both sides get repaired at the same time. That's the only way to do it when the terminals are in that plastic box and you can't see the solder under that box.

If you have terminals that are crimped to the circuit board, vibration is going to cause them to loosen over time. Shine up the terminals and the copper traces right where the terminals go through it, then melt some solder to the connections. Here too, there can be additional copper traces on the backside. The solder should flow through the hole and get to the back traces. No need to solder on both sides.

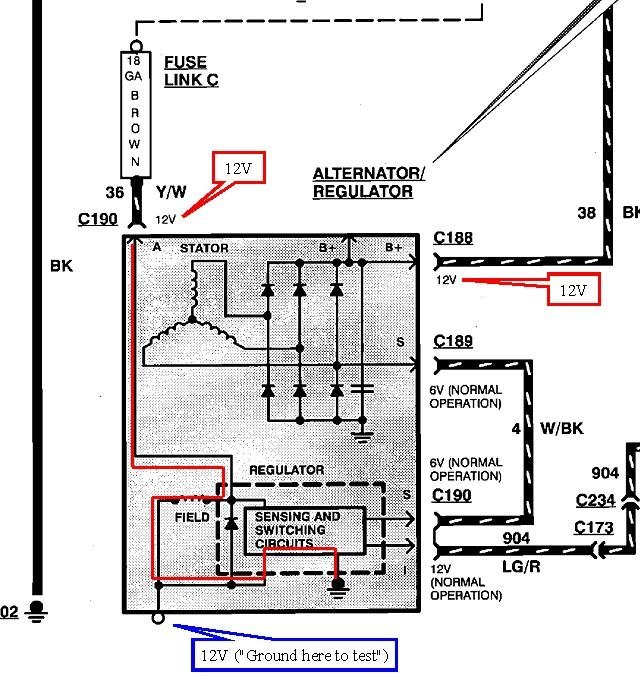

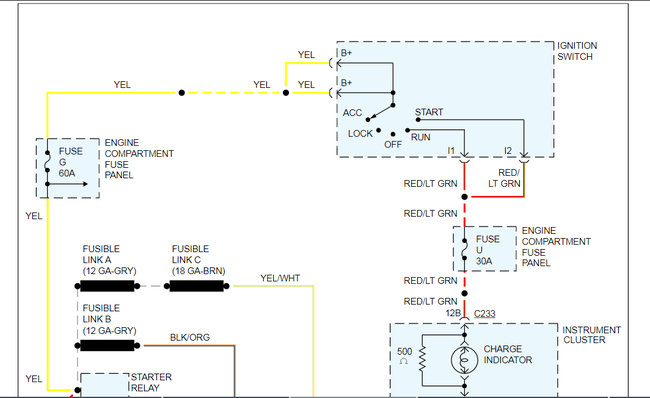

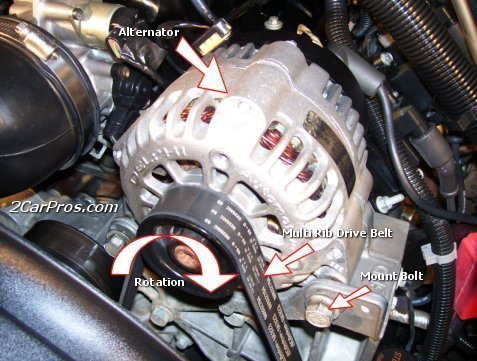

We kind of jumped ahead by not actually diagnosing this yet. The first thing to do is to unplug the three-wire connector at the generator, turn the ignition switch to "run", then check for 12 volts on the light green / red wire. You found 0 volts on there originally, but I'm betting that was with the plug connected. If you find 12 volts now, use a paper clip and / or jumper wire and ground that wire. Doing so should make the "Battery" light turn on. If it does, that entire circuit is okay, and the suspects are that terminal is stretched in the plug so it's not making contact with the mating terminal in the regulator's plug, or the regulator is defective. There are other tests we can do on the regulator and internal brushes, but that would be the plan of attack if you had found 2 volts on the light green / red wire. We'll know more once you check for voltage with plug disconnected.

If the "Battery" light doesn't turn on when you ground the light green / red wire, see if you can figure out which is the red / light green wire feeding that bulb from the ignition switch, then check that one for 12 volts. If it's missing there, a good suspect would be the connector at the base of the steering column. Those terminals often get hot and degraded. There's only a small fraction of an amp flowing through the light bulb. That by itself isn't enough to overheat a terminal, but that circuit coming from the ignition switch is feeding other things that could be drawing high current.

It only takes one tiny strand of wire, or a carbon track around a burned pair of mating terminals to pass enough current for a digital voltmeter to detect 12 volts, but you won't get enough current to turn on the voltage regulator. This often makes digital voltmeters give false readings. If you use a test light instead, they work by using current from the circuit under test, so they will be more accurate for this type of problem. If you can't get enough current to turn on the regulator, the test light won't light up either. The disadvantage of the test light is it doesn't show the exact voltage, but that's not important here. We just need to know if we have something or nothing.

As for chemicals, the only place I use rubbing alcohol is for cassette player heads. It will melt most plastic parts including flexible circuits. For car radios with sealed volume controls that don't work or make the volume change the wrong way, I have a special contact cleaner I call "nuclear waste" so people will leave it alone. It cost my boss $55.00 for one gallon in the mid '80s, but it hasn't been available since then. He gave me enough to fill a little squeeze bottle. That will have to last me the rest of my life. One drop will fix a volume control after soaking in for a few minutes. Regular contact cleaners evaporate too quickly.

For the copper circuits and terminals that need to be shined up, I would use "Tuner Cleaner" which is a special cleaner we used on the old mechanical tv channel selectors. That was another one of our common jobs. Today, rather than run around my shop trying to find a can of that stuff, I just use my fingers to wipe off any powder left from sanding the points. With all the electronics I repair, I really don't use chemicals very much.

Saturday, October 26th, 2019 AT 4:21 PM